I have played The Secret of Monkey Island up to the middle point since its recent release on digital services, and have been enjoying it about as much as expected. As a newcomer to the series, I was not only interested in the puzzles and humor, but also in the quirks of design and writing that would probably never find their way in today's commercial productions (but that the re-issue tactfully doesn't attempt to resolve). And as I suppose was the case for many other gamers, I have also treated myself to the delightful first episode of Tales of Monkey Island, whose synchronized release was a move of genius on the part of Telltale and Lucasarts. This particular game contained hints of decidedly modern design sensibilities, but also played without a doubt to some old-school conventions that I felt worked to its advantage. Curiously enough, these two gaming experiences did not inspire thoughts on the evolution of graphic adventure games proper, but more specifically on their use of sound and visuals. Let me elaborate some more.

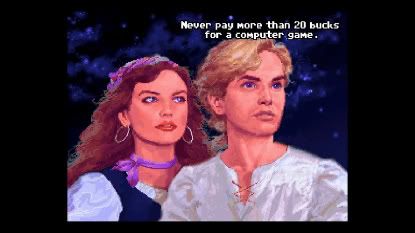

One of the biggest selling points for The Secret of Monkey Island: Special Edition, of course, was its complete aesthetic make-over ; one that would propose a fresh look for the classic game, but retain its special brand of quirky charm. I don't know how it is for returning players (especially those who experienced the game with a functional brain back in 1990), but I find the greatest pleasure in systematically comparing the screens and trying to understand the stakes of the adaptation. What I didn't expect, however, was how clearly I would come to gravitate towards the old packaging, occasionally resorting to the new one for sensory enjoyment but not so much for gameplay purposes. I think there are several reasons for this, but suffice to say for now that I think the original version of Lucasarts' game was perfectly fine as it was, and that it may have actually lost some essential bits in the translation.

Tales of Monkey Island, for its part, confidently casts the graphic adventure series in the intimidating world of modern 3-D, just as Telltale previously did with its delightful Sam & Max episodes. But as great as this bound seems (computer graphics having come a long way since 2000's polygonal Escape from Monkey Island), what is especially pleasing about this rebirth is how understated it really comes off as: clean, unadorned textures, sparse environments and simple special effects constitute a visual design of minimal clutter and maximal efficiency. While budget concerns and limited technology were no doubt a factor in this output, there is a restrained mastery at work in the details and general tone ; an expertise that also transfers to the sound design, and more specifically to the voice work. In this regard, one need look (or hear) no further than the amusing prologue to witness the nuance and liveliness in Dominic Armato's performance of Guybrush Threepwood, accompanied by formidably expressive character animations. Some facial mannerisms may be overused, and Flotsam Island's denizens may look a little too alike, but there is a definite current of cohesion emanating from the game's overall presentation.

How ironic is it, then, to realize that this first episode of the series (subtitled Launch of the Screaming Narwhal) possibly didn't even need polygonal graphics and sophisticated sounds to function on the most basic level. Its camera angles are preset and passive, while its puzzles do not require advanced tridimensional navigation ; its few audio-based trials, apart maybe from a clever treasure hunt, could have been reduced to a few select cues, while its dialogue could have been just as easily read as text. It may be a slippery slope to step on, and this theory might shatter under the slightest bit of scrutiny, but let's throw this out anyway: in purely mechanical terms, I have no reason to believe that this modern-day Monkey Island wouldn't have sustained to be made using the founding SCUMM engine. Heck, it could probably function as a text adventure game and still retain much of its comic and ludic qualities. But that would turn it into a pretty different game now, wouldn't it...

The fact of the matter is this: all manners of graphic adventure games, from the early Sierra classics (also re-issued lately), to the 3-D iterations like Grim Fandango or Syberia, to the more recent gems authored in the Adventure Game Studio engine, rely on the same basic principles of cinematic language. Panning of the camera (be it horizontal scrolling or actual rotation of the virtual viewpoint), cuts from one space to another, shot-countershot exchanges for dialogues, high- and low-angle shots, scaling of depth ; all these figures have been employed to varying degrees of prominence over the history of adventure games, and mostly for the same purposes. On the one hand, in the same way that cinema and other representational mediums, the best uses of these features have enabled developers to yield images of evocative form, lifelike portrayals, and other manners of optic stimulation. Moreso than film, however, the basic requirement of the picture in adventure games is to efficiently transmit useful information to the "viewer" ; a role that the film image clearly shares, but not to the point of interrupting the story's progression in the case of fallacy. Both of these functions depend mostly on the inventive and capable use of computer graphics software, regardless of which techno-asset is presently deemed to be "state of the art".

Production values, then, mainly serve the purpose of crafting a compelling aesthetic experience for the user, which is probably not as negligible a component as I make it sound. While it will occur that a game's engine influence the core design of its puzzles, the usual goal will be to add style and form to what initially amounts to a cold mechanical construction. The only condition to this creative effort is that the art do not get in the way of the gameplay's unfolding ; in this regard, one need only look to the hugely-buzzed Time Gentlemen, Please! for an excellent example of a project's flow and tone being unobstructed and even complimented by "limited" resources and abilities (to say the least). As for any works of art, graphic adventure games demand to be judged on their own terms rather than according to the standards of the present day, which is exactly why the original Secret of Monkey Island can still be considered a great success of visual implementation: reduced to the top half of the screen, the playfield allows for denser images and less chances of missing information, while the bottom portion, unquestionably showing its age today, still proves to facilitate interaction with immediate feedback and effortless browsing. From this simple but solid foundation, it's really all about peppering the game world with fanciful touches that make it come alive, or signify, or otherwise amuse and dazzle.

Which brings me to the very serious problems I have with the Secret's 2009 make-over. On the surface, certainly, this reinvention would seem to have it all: its painterly vistas are lush and sprawling, while its atmospheric soundscapes inject the various maritime locales with a much greater sense of place than before. On a larger scale, it can also be credited for greater aesthetic consistency than its early-90's counterpart, which fell flat in its few attempts to depict some of its cartoonish characters as realistic figures. Try to play the game in this mode for more than five minutes, however, and you may begin to feel that something is off: names of pointed objects and possible interactions are displayed in small, pale lettering in the bottom corners of the screen, replacing the clear purple-on-black of yore ; verb command and inventory boxes are displayed one at a time, using separate keyboard buttons, which not only shatters the former iteration's mouse-only integrity, but turns object manipulation into an absolute pain. Interface issues aside, technical requirements may prevent some computers to run the game at a proper pace without sacrificing precious resolution, and make the overall manipulation overly clunky and laborious. The thing here is not so much that the "special edition" of Monkey Island features a "bad" interface ; it is simply that the contrast emphasizes the former's relative strengths.

Even the voicing of the Secret's original script, which I will not get too much into at this point, is up for debate: since Gilbert, Schafer and Grossman's uncredited lines and gags were specifically written to be read, many of them (especially those involving grunting and random onomatopeia) simply don't convert very well to sound, while the cast's readings (including Armato's), without the support of elaborate animations, most often come off stilted and laboured, as if restricted by the imperative of faithfulness. This is not a matter of being an "old school", "lo-fi" evangelist ; it is simply recognizing that the "modernizing" of certain aspects of a game can often grow superfluous, especially if it comes to the point of affecting playability, which is often the case here. While Lucasarts' talented groups of artists may have devised a pleasing cutout style reminiscent of René Laloux's films or Monty Python's animated segments, they have reduced the functionality of what was already a spectacular display of pixel drawing compensating for the deficiencies of its day, as well as the imaginative power the original required to fill its blank spots. And while their restraint was undeniably wise, it hasn't translated into the same pitch-perfect beauty as Telltale's effort: a more ambitious work, also flawed in its execution, but at least strong enough to function on its own terms. As it stands, The Secret of Monkey Island: Special Edition contains an interesting case of internal dichotomy that is worthy of any gamer's attention, but I would be surprised if its attractive new coat of paint sufficed to turn new, rabid audiences on to the franchise's history for more than a brief stint.

One of the biggest selling points for The Secret of Monkey Island: Special Edition, of course, was its complete aesthetic make-over ; one that would propose a fresh look for the classic game, but retain its special brand of quirky charm. I don't know how it is for returning players (especially those who experienced the game with a functional brain back in 1990), but I find the greatest pleasure in systematically comparing the screens and trying to understand the stakes of the adaptation. What I didn't expect, however, was how clearly I would come to gravitate towards the old packaging, occasionally resorting to the new one for sensory enjoyment but not so much for gameplay purposes. I think there are several reasons for this, but suffice to say for now that I think the original version of Lucasarts' game was perfectly fine as it was, and that it may have actually lost some essential bits in the translation.

Tales of Monkey Island, for its part, confidently casts the graphic adventure series in the intimidating world of modern 3-D, just as Telltale previously did with its delightful Sam & Max episodes. But as great as this bound seems (computer graphics having come a long way since 2000's polygonal Escape from Monkey Island), what is especially pleasing about this rebirth is how understated it really comes off as: clean, unadorned textures, sparse environments and simple special effects constitute a visual design of minimal clutter and maximal efficiency. While budget concerns and limited technology were no doubt a factor in this output, there is a restrained mastery at work in the details and general tone ; an expertise that also transfers to the sound design, and more specifically to the voice work. In this regard, one need look (or hear) no further than the amusing prologue to witness the nuance and liveliness in Dominic Armato's performance of Guybrush Threepwood, accompanied by formidably expressive character animations. Some facial mannerisms may be overused, and Flotsam Island's denizens may look a little too alike, but there is a definite current of cohesion emanating from the game's overall presentation.

How ironic is it, then, to realize that this first episode of the series (subtitled Launch of the Screaming Narwhal) possibly didn't even need polygonal graphics and sophisticated sounds to function on the most basic level. Its camera angles are preset and passive, while its puzzles do not require advanced tridimensional navigation ; its few audio-based trials, apart maybe from a clever treasure hunt, could have been reduced to a few select cues, while its dialogue could have been just as easily read as text. It may be a slippery slope to step on, and this theory might shatter under the slightest bit of scrutiny, but let's throw this out anyway: in purely mechanical terms, I have no reason to believe that this modern-day Monkey Island wouldn't have sustained to be made using the founding SCUMM engine. Heck, it could probably function as a text adventure game and still retain much of its comic and ludic qualities. But that would turn it into a pretty different game now, wouldn't it...

The fact of the matter is this: all manners of graphic adventure games, from the early Sierra classics (also re-issued lately), to the 3-D iterations like Grim Fandango or Syberia, to the more recent gems authored in the Adventure Game Studio engine, rely on the same basic principles of cinematic language. Panning of the camera (be it horizontal scrolling or actual rotation of the virtual viewpoint), cuts from one space to another, shot-countershot exchanges for dialogues, high- and low-angle shots, scaling of depth ; all these figures have been employed to varying degrees of prominence over the history of adventure games, and mostly for the same purposes. On the one hand, in the same way that cinema and other representational mediums, the best uses of these features have enabled developers to yield images of evocative form, lifelike portrayals, and other manners of optic stimulation. Moreso than film, however, the basic requirement of the picture in adventure games is to efficiently transmit useful information to the "viewer" ; a role that the film image clearly shares, but not to the point of interrupting the story's progression in the case of fallacy. Both of these functions depend mostly on the inventive and capable use of computer graphics software, regardless of which techno-asset is presently deemed to be "state of the art".

Production values, then, mainly serve the purpose of crafting a compelling aesthetic experience for the user, which is probably not as negligible a component as I make it sound. While it will occur that a game's engine influence the core design of its puzzles, the usual goal will be to add style and form to what initially amounts to a cold mechanical construction. The only condition to this creative effort is that the art do not get in the way of the gameplay's unfolding ; in this regard, one need only look to the hugely-buzzed Time Gentlemen, Please! for an excellent example of a project's flow and tone being unobstructed and even complimented by "limited" resources and abilities (to say the least). As for any works of art, graphic adventure games demand to be judged on their own terms rather than according to the standards of the present day, which is exactly why the original Secret of Monkey Island can still be considered a great success of visual implementation: reduced to the top half of the screen, the playfield allows for denser images and less chances of missing information, while the bottom portion, unquestionably showing its age today, still proves to facilitate interaction with immediate feedback and effortless browsing. From this simple but solid foundation, it's really all about peppering the game world with fanciful touches that make it come alive, or signify, or otherwise amuse and dazzle.

Which brings me to the very serious problems I have with the Secret's 2009 make-over. On the surface, certainly, this reinvention would seem to have it all: its painterly vistas are lush and sprawling, while its atmospheric soundscapes inject the various maritime locales with a much greater sense of place than before. On a larger scale, it can also be credited for greater aesthetic consistency than its early-90's counterpart, which fell flat in its few attempts to depict some of its cartoonish characters as realistic figures. Try to play the game in this mode for more than five minutes, however, and you may begin to feel that something is off: names of pointed objects and possible interactions are displayed in small, pale lettering in the bottom corners of the screen, replacing the clear purple-on-black of yore ; verb command and inventory boxes are displayed one at a time, using separate keyboard buttons, which not only shatters the former iteration's mouse-only integrity, but turns object manipulation into an absolute pain. Interface issues aside, technical requirements may prevent some computers to run the game at a proper pace without sacrificing precious resolution, and make the overall manipulation overly clunky and laborious. The thing here is not so much that the "special edition" of Monkey Island features a "bad" interface ; it is simply that the contrast emphasizes the former's relative strengths.

Even the voicing of the Secret's original script, which I will not get too much into at this point, is up for debate: since Gilbert, Schafer and Grossman's uncredited lines and gags were specifically written to be read, many of them (especially those involving grunting and random onomatopeia) simply don't convert very well to sound, while the cast's readings (including Armato's), without the support of elaborate animations, most often come off stilted and laboured, as if restricted by the imperative of faithfulness. This is not a matter of being an "old school", "lo-fi" evangelist ; it is simply recognizing that the "modernizing" of certain aspects of a game can often grow superfluous, especially if it comes to the point of affecting playability, which is often the case here. While Lucasarts' talented groups of artists may have devised a pleasing cutout style reminiscent of René Laloux's films or Monty Python's animated segments, they have reduced the functionality of what was already a spectacular display of pixel drawing compensating for the deficiencies of its day, as well as the imaginative power the original required to fill its blank spots. And while their restraint was undeniably wise, it hasn't translated into the same pitch-perfect beauty as Telltale's effort: a more ambitious work, also flawed in its execution, but at least strong enough to function on its own terms. As it stands, The Secret of Monkey Island: Special Edition contains an interesting case of internal dichotomy that is worthy of any gamer's attention, but I would be surprised if its attractive new coat of paint sufficed to turn new, rabid audiences on to the franchise's history for more than a brief stint.

No comments:

Post a Comment